Understanding Dementia: Memory Tests and Early Physical Signs

Overview and Outline: Why Early Detection Matters

Dementia does not arrive like a storm; it ebbs in, rearranging routines, nudging memory, and sometimes tightening balance and coordination. Understanding what to look for—and how tests are used—helps families move from uncertainty to practical steps. Globally, tens of millions live with dementia, and millions more develop it each year. Earlier recognition does not cure the condition, but it can ease planning, improve safety, and open access to proven supports. This article sets the stage with a clear roadmap, then dives into the tools clinicians use, the meaning of memory tests, and the early physical signs that often go unnoticed.

Here is the outline we will follow, so you know where you are headed before you set out:

– What early detection can and cannot achieve, and why timing matters

– How screening tests differ from full diagnostic workups, and what each step typically includes

– What memory tests actually measure, how scores are interpreted, and their limitations

– The early physical signs that can accompany cognitive change, including gait and coordination shifts

– Practical next steps for families: preparing for appointments, tracking changes, and supporting day-to-day function

Early recognition is meaningful for several reasons. First, it allows evaluation for medical issues that can mimic or worsen cognitive symptoms—such as thyroid imbalance, vitamin deficiencies, sleep apnea, depression, medication side effects, or poorly controlled cardiovascular risk factors. Second, it gives space to address safety questions—driving, finances, medication management—before a crisis. Third, research shows that tailored exercise, cognitive engagement, hearing and vision support, and management of blood pressure and diabetes can help maintain function and quality of life. While no single test defines a person’s future, a thoughtful process rooted in evidence can illuminate a safer, steadier path.

Throughout the sections that follow, you will find practical comparisons—normal aging versus worrisome change, brief screens versus comprehensive evaluations, recall versus recognition—so you can interpret observations in context. Along the way, we will translate clinical language into everyday terms and sprinkle in clear examples you can picture at the kitchen table. Think of this guide as a reliable map rather than a crystal ball: it will not predict every turn, but it will keep you oriented and prepared for the road ahead.

Dementia Tests: Screening, Diagnostic Pathways, and What to Expect

When concerns arise, the first step is often a brief screening test administered in a clinic or primary care office. Screens are quick—typically 10–15 minutes—and sample multiple abilities: orientation, attention, short-term memory, language, and simple visuospatial tasks. Their role is triage. A lower-than-expected score suggests the need for more detailed evaluation; a reassuring score does not always rule out subtle impairment, especially in highly educated individuals or those masking difficulties with routines. In other words, screening tools are sensitive but not definitive.

A diagnostic pathway is more comprehensive. Clinicians take a detailed history, often with input from a family member who can describe day-to-day changes. A physical and neurological exam helps identify signs pointing toward specific causes. Laboratory tests may check thyroid function, B12 levels, markers of infection or inflammation, and metabolic factors. Hearing and vision assessments are important, because sensory loss can mimic cognitive problems. In many cases, brain imaging is ordered to look for strokes, significant atrophy patterns, hydrocephalus, or other structural issues. When the picture remains unclear, referral for formal neuropsychological testing can provide a nuanced profile of strengths and weaknesses across memory systems, attention, language, visuospatial skills, and executive function.

Consider how clinicians balance sensitivity and specificity. A brief screen aims to catch as many concerning cases as possible (higher sensitivity), accepting some false alarms. A full workup aims to classify the type of cognitive disorder (higher specificity), considering the whole story: onset, rate of change, medical context, and functional impact. Clinicians also factor in depression, sleep disturbance, pain, and medication lists—common confounders that can lower scores.

Expect the process to be collaborative. Bring a timeline of changes, examples of slipped tasks, and a list of medications and supplements. Note fluctuations: are symptoms stable, worse at night, or clearly tied to illness or stress? Such details sharpen the differential diagnosis. Common scenarios include mild cognitive impairment, a condition in which daily function is largely preserved but measurable deficits appear on testing; progression risk varies, with annual conversion to dementia higher in specialty clinics than in community samples. For some, results point toward vascular contributors; for others, toward degenerative patterns or reversible factors. The destination is not a single number, but a shared plan aligned with the person’s values and needs.

Memory Tests: What They Measure, How They Differ, and How to Read the Signals

Memory tests are often portrayed as riddles with right or wrong answers, but they are better understood as lenses. Each lens samples a particular memory system or related cognitive process. Immediate recall tasks test registration—can a person encode a short list of words right now? Delayed recall checks storage and retrieval—after a distraction, what returns without prompting? Recognition adds cues—can a person identify target items among choices? Differences between free recall and recognition can hint at whether the challenge lies in retrieval strategy or in the memory trace itself.

Verbal list learning, story recall, and paired associations assess new learning over repeated trials. Visuospatial memory tasks use designs or simple figures to probe nonverbal encoding. Attention and working memory are gauged through digit sequences or sequencing exercises. Executive functions—planning, set-shifting, inhibition—are sampled with tasks that require switching rules, generating words in categories, or solving multistep problems. Even the humble “copy this shape” exercise taps visuoconstruction and visual scanning, which in turn influence memory performance. The point is that a single score never tells the whole story; patterns matter.

Interpreting results requires context. Age, education, cultural background, and primary language influence test performance. Hearing and vision issues can depress scores; so can anxiety or fatigue on test day. Practice effects—improvement simply from familiarity—can raise scores on repeat testing, while intercurrent illness can lower them. That is why clinicians often prefer comparing multiple domains and tracking change over time rather than making conclusions from a single sitting.

To make this concrete, imagine two individuals with the same delayed recall score. Person A shows poor initial learning but benefits from cues, suggesting that attention or strategy may be the bottleneck. Person B learns well initially yet fails delayed recall and recognition, pointing to storage weakness. Their daily supports would differ accordingly. One might benefit from structured note-taking and reduced distractions; the other might rely more on external memory aids and routine-based cues.

What about “normal aging”? Slower retrieval and occasional word-finding are common; relying on reminders for names or shopping lists is not unusual. Worrisome patterns include frequent misplacement that is not resolved by retracing steps, getting lost in familiar places, or repeating questions within short intervals without awareness. Memory tests help separate expected changes from signs that warrant further evaluation. Used thoughtfully, they become instruments for clarity, not verdicts.

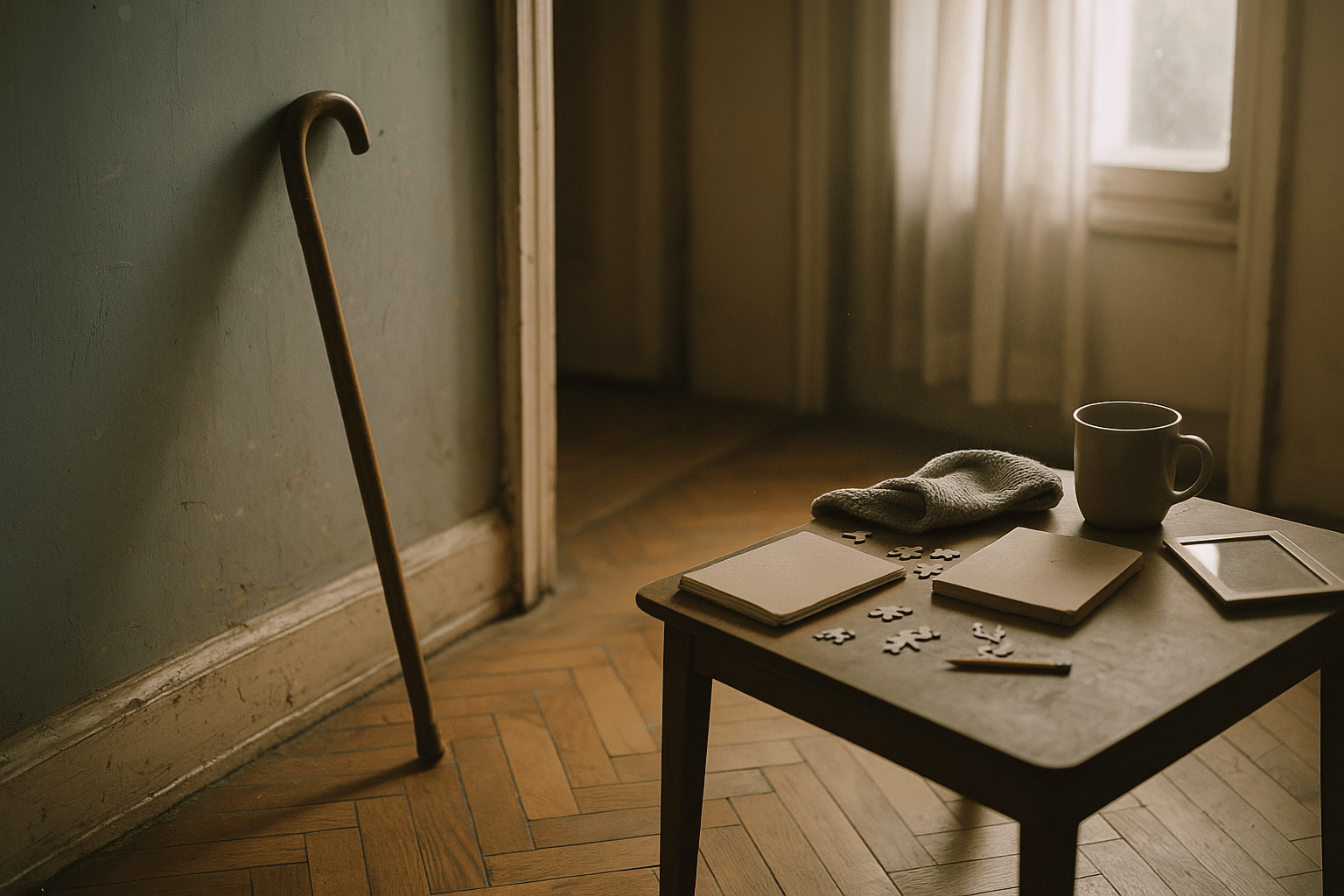

Early Physical Signs of Dementia: What the Body May Whisper Before It Shouts

Cognition and movement are intertwined. Long before dramatic forgetfulness appears, some people exhibit subtle physical shifts that reflect changes in brain networks integrating movement, attention, and perception. Family members may notice a slightly slower walking pace, a narrower step pattern, or reduced arm swing. Balance may feel less sure on uneven ground. Fine motor tasks—buttoning, handling coins, opening jars—may take longer or feel clumsier even when strength seems intact. None of these signs diagnoses dementia on its own, but together they can form a meaningful pattern.

Research has linked gait speed and variability to cognitive health. Slowed pace and increased stride-to-stride inconsistency, especially during “dual-task” walking (for example, walking while counting backward), have been associated with higher risk of cognitive decline. Spatial navigation can also change early: misjudging turns in unfamiliar buildings or overshooting doorways. Visual processing shifts may appear as difficulty tracking fast-moving objects or misplacing items that are in plain sight. Hand-eye coordination can feel less automatic; familiar recipes may require a recipe card nearby not because the dish is forgotten, but because sequencing steps is harder under time pressure.

Physical clues often cluster with other signals. Consider these patterns:

– A new, shuffling walk and frequent near-falls when turning corners

– Hesitation at thresholds, curbs, or escalators despite adequate leg strength

– Difficulty setting a consistent pace during neighborhood walks, especially while chatting

– New bumps and scrapes on door frames or furniture edges from misjudged distances

– Increasing time to dress, including mixing up steps like socks before pants

It is important to distinguish these signs from those caused by arthritis, inner ear disorders, medication side effects, or peripheral neuropathy. A clinician can evaluate for those conditions and, when needed, refer to physical therapy. Targeted exercises can improve balance and confidence, and a home safety review can reduce fall risk. Notably, addressing hearing and vision loss can improve both gait and cognitive testing performance by reducing the cognitive load of poor sensory input.

The takeaway is not to become alarmed by every stumble, but to notice patterns over time. When physical changes emerge alongside new memory lapses or planning difficulties, it is reasonable to seek evaluation. Early conversation often leads to simple, practical adjustments—better lighting, clearer contrasts on stairs, footwear with good traction, and routines that reduce multitasking during complex movements. The body is often the first messenger; listening carefully can make daily life smoother and safer.

From Concern to Action: Preparing for Appointments, Tracking Changes, and Building a Supportive Plan

Turning concern into a plan begins at home. The most valuable “test” you can bring to an appointment is a concise record of what has changed and when. Create a timeline with examples, not just impressions: missing two bill payments in April, repeating the same question at lunch and again ten minutes later in May, stumbling twice on the back steps in June. Add notes on sleep, mood, appetite, new stressors, and any illnesses. This narrative anchors test results in real life and helps clinicians target the right next steps.

Preparation also reduces stress on the day of testing. Bring glasses and hearing devices, a list of medications and supplements, and a recent blood pressure log if you have one. Plan for an unhurried visit and a small snack afterward to avoid fatigue. If possible, invite a trusted person who can share observations and provide support. Small details make a difference. For example, if the room is quiet and well lit, test performance better reflects cognition rather than sensory strain.

After results are discussed, the question is “what now?” Think in layers:

– Address reversible contributors: sleep apnea assessment, mood treatment, medication review, hearing and vision care

– Manage cardiovascular risks: blood pressure, glucose, and lipid control under medical guidance

– Build daily routines: consistent wake times, regular meals, and predictable anchors for medications and activities

– Engage the body and mind: brisk walking, strength and balance exercises, and cognitively engaging hobbies

– Simplify the environment: pill organizers, labeled storage, and clutter reduction for clearer navigation

Care partners benefit from structure, too. Share responsibilities, set up reminders, and agree on check-in times. Consider discussing legal and financial planning early, while decision-making is strong. Community resources—support groups, occupational therapy, driving assessments, and home safety evaluations—can extend independence and reduce caregiver strain. Technology can help if chosen thoughtfully: large-button phones, voice reminders, and simple location-sharing between consenting adults can add a layer of reassurance without overwhelming complexity.

Finally, remember that change is rarely linear. Good days and harder days will alternate. Tracking patterns across weeks or months is more informative than reacting to a single off day. Make room for joy in routine: music that invites movement, photographs that invite stories, and short visits that end before fatigue sets in. None of these steps claims to cure cognitive disorders. Together, however, they create a steadier platform from which to navigate tests, results, and the practical choices that follow.